The tribe has spent years trying to restore the species, and tribal executive committee member Dan Kane fears that dredging could undo that progress. The tribe’s primary concern is that dredging will wreak havoc on lamprey larvae, which bury themselves in sediment. Though the Corps has timed its dredging to minimize harm to endangered salmon and steelhead, the nearby Nez Perce Tribe is worried about damage to another fish: Pacific lamprey, the prehistoric, eel-like creatures whose populations have been ravaged by dams. “We’re long overdue, and the situation has gotten pretty bad.”īut this is the Snake, one of the most politically fraught rivers in the country, a waterway where even seemingly routine maintenance is anything but. “Most navigation channels require dredging every two or three years,” says Kristin Meira, executive director of the Pacific Northwest Waterways Association. The Ice Harbor Dam is one of two sites being dredged. Though the Corps has a congressional mandate to keep the channel 14 feet deep, Port of Clarkston manager Wanda Keefer recently said it’s down to 7 feet in some places, and barges have run aground. But the Snake hasn’t been dredged since 2006, and sediment has built up, especially at its confluence with the Clearwater River.

Last year, some 3 million tons of commodities - lentils, timber, wheat and other goods - were barged down the river.

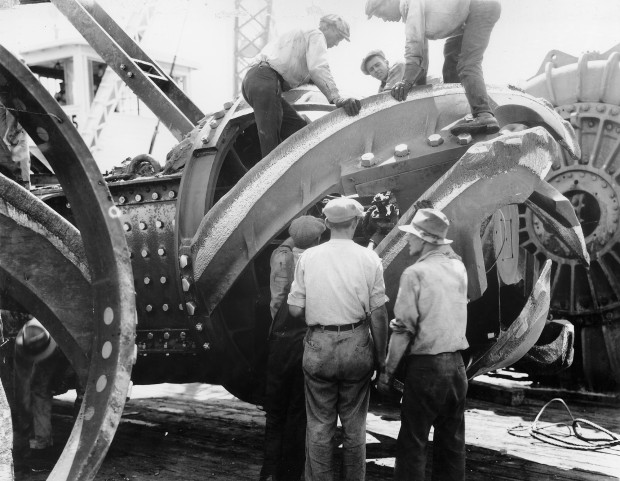

Army Corps of Engineers had begun dredging the Snake - a project the agency claims will preserve the economic viability of the river’s ports, and which environmentalists say is just another harmful boondoggle on a river that’s seen too many of them.įor the feds, mucking out the Snake is a no-brainer. For the first time in nine years, the U.S. On the morning on January 12, not far from the Idaho-Washington border, a clawlike dredge descended from a crane, scooped up a wad of sediment from the bottom of the Snake River, and dumped the sludge into the bed of a waiting barge. Like Tweet Email Print Subscribe Donate Now

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)